Sneakers: The Original Zero-Drop Shoe

“Oh, you scared me! I didn’t hear you come in the room.”

“Yeah – I sneaked up on you… wearing my new sneakers.”

In fact, that’s how sneakers got their nickname; in the early 1900s they were a new kind of shoe, not with the traditional leather sole, but instead with rubber soles, and with a new kind of rubber: vulcanized rubber. People knew about rubber for a long time; it was the sap of a tropical tree and when warm was a gooey blob, and when cold, brittle. (Specifically, latex is the milky, liquid sap from rubber trees, while rubber is the processed, solid, elastic material made from this latex.) But a struggling inventor, Charles Goodyear was experimenting with rubber when in 1839, he accidentally got some sulphur on it and heated it. When it cooled down, it was pliable… and nearly indestructible. Patenting his invention in 1844 as “vulcanized rubber” (named after Vulcan, the Roman god of fire), you’d think it would have made Goodyear a millionaire, but he died penniless, beset by legal woes and patent infringements. But the cat was out of the bag, and now people tried to figure out what this vulcanized material could be used for. If they could look into the future, they would have been making and stockpiling automobile tires! But of course there was another place where rubber could meet the road – shoes.

The vulcanization technique used heat to create a strong, permanent bond between the rubber sole and the shoe’s upper material (like canvas or suede). This eliminated the need for glues or complex sewing methods used with leather soles, streamlining mass production.

The Plimsoll

One of the first shoe designs that had rubber soles was called a “plimsoll.” Originally designed as “sand shoes” for use at the beach or general leisure activities, it was called a plimsoll because the colored horizontal band where the rubber sole met the canvas upper resembled the Plimsoll line on the outside of a ship’s hull, indicating the maximum safe loading depth. If water went over that line, the wearer’s feet would get wet.

The shoe’s water resistance and grip made them a popular choice for early recreational sports like croquet and tennis. Initially, they were a luxury item for the wealthy who had the leisure time for recreational sports. It wasn’t until later in the century and early 1900s that they became mass-produced and affordable for the general population. It was the first “modern” zero-drop shoe – modern in the sense that for millennia, zero-drop ruled in the guise of moccasins and sandals. (And that “plimsoll” line is still part of the classic Chucks, albeit as only a design detail.)

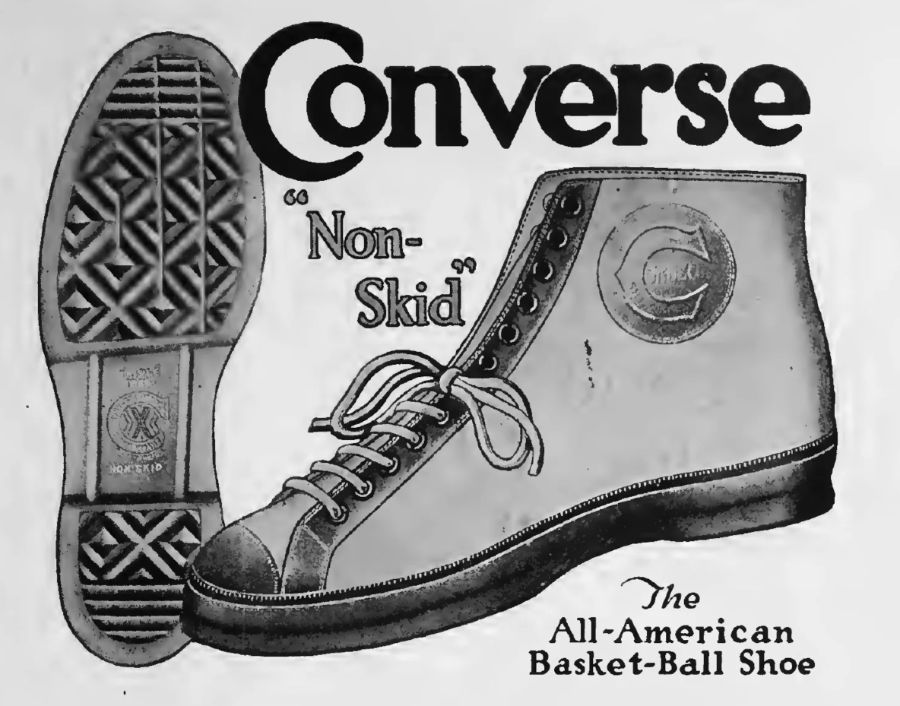

→ Shop for Barefoot Shoes! →Speaking of which, Converse was one of the first large commercial makers of sneakers, starting in 1917. U.S. Rubber’s Keds line was its main competitor, starting a year earlier. Initially marketed as a tennis and general athletic shoe, primarily for women, the Keds were low-top and originally available in brown canvas with black trim.

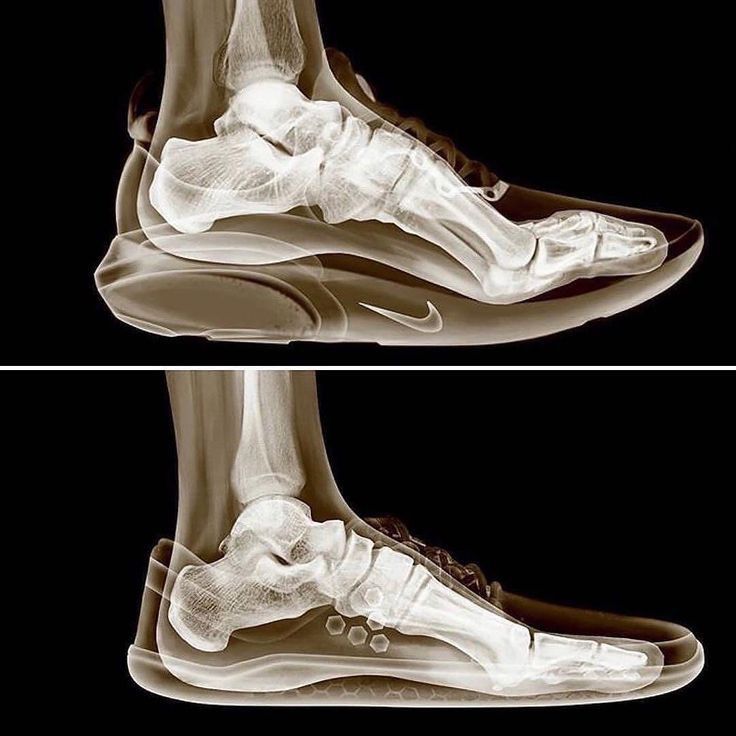

Sneaker Design

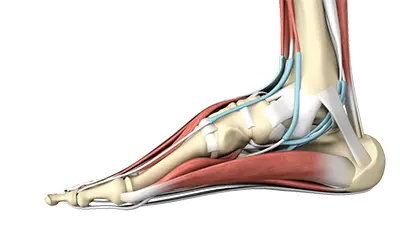

Both Converse and Keds were zero-drop (no heel rise). But they didn’t have the classic modern barefoot-shoe, wide anatomically correct toebox. There is no clear evidence that early sneaker brands like Converse and Keds consciously rejected an anatomically wide toebox for biomechanical reasons. The design choices seem driven more by manufacturing simplicity, aesthetics, and sport norms of the time than by any explicit decision to avoid natural toe splay.

Surviving histories and brand narratives about Converse and Keds do not highlight any explicit discussion of “anatomically correct” toeboxes, wide forefoot design, or a deliberate trade-off against natural toe splay. Instead, they frame these shoes as innovative for rubber soles, light weight, and suitability for sport, suggesting the narrow toebox was an unexamined default rather than a researched, intentional anti-anatomical choice.

Enter Chuck

Converse and Keds were doing okay, but it took a retired basketball player who was a natural born salesman to light the rocket fuel: Charles Taylor (everyone called him Chuck) walked into the Converse offices looking for a job. Seeing his innate sales chops, they hired him immediately. And Chuck didn’t just go selling to shoe stores; he contacted high school basketball coaches and set up basketball clinics for their teams. And of course, he sold sneakers. The shoe model he was pushing was one that he had a hand in designing for Converse – the shoe that bears his signature on every ankle patch – the “All Star,” better known today as Chucks. The high top design, with its ankle support, was perfect for basketball, a new sport catching on at the time. His ankle patch signature was added in 1932.

While Converse and Keds were the first major brands, other companies in the early 1900s scrambled to cash in on this growing market. The die was cast: the ability to mass-produce reliable, comfortable, and affordable rubber-soled shoes, led to the massive growth of the “athletic” shoe market, especially starting in the 1970s with the advent of modern cushioned designs and the new top dogs: Nike, Reebok, Addidas, et al.

It took the shoe industry decades to re-invent the wheel with what was marketed as “barefoot shoes” – an oxymoron that stuck.

(This post was compiled in part by using AI.)